It was the closest spectacle to the Carnival in Rio and the Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Except that it was not on the streets but high above on thousands of rooftops and up in the limitless sky. Lahore had the best celebration of the nation in its Basant; the colourful and vociferous spring festival held in early February. It is a welcome development that after a prohibition of seventeen years, it is back to life. A whole generation of Lahore, Kasur and Gujranwala in particular and of Punjab in general, has grown up without knowing the joys of kite flying. That drought is going to end in February.

Born in Gawalmandi and raised in Gumti Bazaar in the 1950s and 60s, kite flying was an integral part of this Lahori’s youth. It was also considered a genuine sport with cricket taking a distant third behind hockey. We Lahoris were very proud of this activity. As a young twelve-year-old lad, this author appeared for an interview before a board headed by Mr Catchpole, the legendary British founding-principal of Cadet College Hassanabdal, the then principal of PAF Public School Sargodha and subsequently a long time teacher of English in Abbottabad Public School. When asked what he did in his spare time, the young boy delightfully replied, to the bewilderment of the Principal, that he flew kites. Only later in the interview, this author revealed, to the visible pleasure of Mr Catchpole, that he also collected stamps – the genuine pastime of a typical British schoolboy!

The Walled City of Lahore even has a saint of kites. He is believed to have evaded British police in the Fort while descending to safety from sky holding the string of a kite

Although kite flying continued throughout the year, even in the evenings of the hot and humid months, it picked up pace in September and was in full swing from October to March. Shops with kites in myriad styles became active in every street. The string, called dor or majha, was prepared by professionals in public parks around the city and along the banks of the Ravi. Plain cotton string was plastered with a paste of glue, finely crushed glass and colours, providing the abrasiveness for cutting the strings of other kites.

Every rooftop in the city became alive with children and grownups alike, indulging in the intricacies of pitching one’s kite against others. Every victory or loss was analysed, every move studied and lessons drawn for future contests. This was nothing less than the aerial dogfights between supersonic jets that this author observed later during his Pakistan Air Force (PAF) days. Kite flying competitions were held in the open fields and in Minto Park over the weekends. Some people were so enamoured that they attached currency notes to their kites. People walked in the streets with their eyes glued to the sky watching the kites flying above. There was limitless joy in catching a kite that had been cut loose.

Accidents were many, some being lethal. In his teen, this author cut his right index finger, slightly above the distal interphalangeal crease line. The cut was deep and long, and the 60-year-old scar continues to persist. It is occasionally shown to friends as a badge of honour worthy of a Purple Heart. For one hailing from the walled city, it was a usual rite of passage.

The walled city even has a saint of kites. He is believed to have evaded British police in the Fort while descending to safety from sky holding the string of a kite. His darbar lies on the Fort Road on the right as one walks from Paniwala Talab to Masti Gate. This author used to go to a primary school in the vicinity for about a year and passed by the darbar every day; casting avaricious glances at the stack of kites piled inside by the devotees.

Certain self-styled religious sections in Pakistan think that Basant is a Hindu festival. That is a misconception. It’s an event of the people irrespective of their religious or social affiliations. The self-claimed guardians of Islam in Pakistan have caused many social distortions and their failure to differentiate between religion and culture has infused extremism in the society. These festivities invited the wrath of these zealot Islamists who don’t like people living their own life or exercising their choices, and have their own strange untenable ideas of happiness. People in Lahore didn’t care for their pronouncements.

Happiness is infectious. You laugh and the world laughs with you. That’s what started to happen for Lahoris when the world was caught up with the joy they propagated during Basant. People travelled not only from other parts of the country but from across the globe to participate in the joyful event. The concept of corporate Basant was introduced when large business houses arranged Basant for their clients and associates. Business Basant added a new dimension to the event, projecting a soft image as against the prevailing jihadi culture of the time. Whereas the Lahoris flew their kites during the day time, the main events of corporate Basant were shifted to night. Their activities included much more than kites. They hired rooftops in the galis and bazaars of the walled city where light beams, dancing girls, dhols, band groups, barbecue, liqueur and loud music became part of festivities. It was the best carnival that the nation had witnessed.

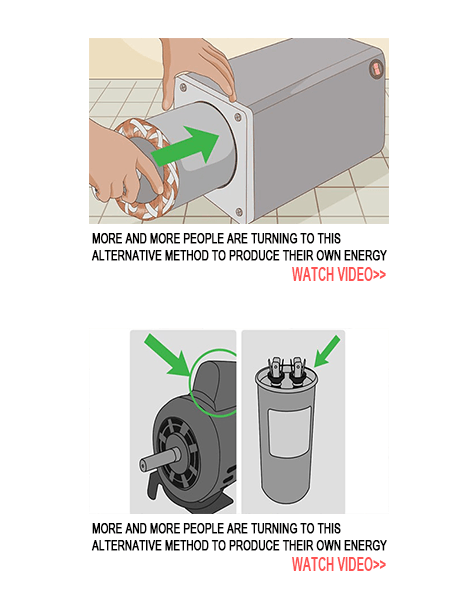

When Basant was banned, the world missed the fun but it was the blue blooded Lahoris like this author who mourned, and continue to mourn, the loss of the festival that united the people. The unnecessary deaths were tragic and cannot be condoned or mitigated by any means. Two factors that contributed to these sad incidents were failure of personal responsibility and implementation of writ of the state. These deaths and injuries resulted for motorcycle riders. All that was required for their foolproof safety was installation of metal or plastic rods that ran from the handle to over the head of the rider. That’s all; nothing more. A device costing a paltry Rs 200 was all that was needed to safeguard the precious lives.

However, neither the people of the city cared nor the government implemented rules for enforcement. After all, drivers of vehicles the world over are required to wear seat belts for safety. The motorcycle rod is a similar device. Basant was a huge business activity worth billions of rupees but a device costing a miserly sum defeated it. The second hazard was of leading metal strings tied to the kite. That was not very common but was a criminal act which required force of law. These were collective failures of governance and civic sense.

Let’s wish the city of Lahore a happy festival. One hopes that the people have the sense to follow the prescribed safety measures so that there are no serious accidents. Punjab government has made elaborate arrangements including free motorcycle safety rods, free public transport and strict enforcement of safety rules. Let kite flying and Basant flourish as a joyful sport.